How Can Socialists Run Cities – will Mamdani show us the way?

Zohran Mamdani’s election to Mayor of New York has been a badly-needed boost to the confidence of the left in the U.S. and beyond. It has also reignited debate about the strategic choices facing socialists elected to local government, and eventually to national governments too. A special, end-of-year issue of Jacobin, the U.S. left magazine, was devoted to lessons of municipal socialism, from Red Vienna and Milwaukee’s ‘sewer socialists’ in the first half of the 20th century, to Communist-run cities in Italy or France after the defeat of fascism and Ken Livingstone’s Greater London Council in the 1980s, facing off, quite literally across the River Thames, against what was then the far-right, Margaret Thatcher, in government.

These are debates that we, too, need to take seriously, as we seek to build Your Party Scotland as a real, socialist alternative, here in Glasgow and across the country.

One of the most suggestive contributions to the discussion draws on experiences of participatory democracy in Latin America and elsewhere, to argue that as mayor, ‘Zohran Needs to Create Popular Assemblies’ (Jacobin 12.22.2025. https://jacobin.com/2025/12/mamdani-popular-assemblies-democratic-socialism) to build a bottom-up political culture that empowers working people. In this article, Gabriel Hetland, who has done a lot of work with social movements in Venezuela and Bolivia, and Bhaskar Sunkara, the editor of Jacobin, point to the positives of governing with such assemblies. In the short term, it enables the social base to keep mobilising, which is vital to sustain a progressive administration that will inevitably be hemmed in by hostile elites and procedural roadblocks, hindering its attempts to implement even its core, immediate, ‘affordability’ policies. In the process of these fights over housing and transport, childcare and the cost of groceries, it also begins to create new structures of power, increasing “the capacity of workers to collectively shape the decisions that shape their lives”, and “to lay the basis for a society beyond capitalism”.

Even without the aid of a crystal ball, it is not hard to see how a socialist administration in Glasgow City Council, or even in Holyrood, would confront many of the same obstacles, and need similar solutions, as it sought to seize back the cost-of-living agenda hijacked by Reform in Scotland, or even confront a far-right, Reform government in Westminster.

As Hetland and Sunkara make clear, the key point of assemblies or other forms of mass, participatory democracy, is to change the relationship between the governed and their government, shifting power back to the former. The forms this can take vary greatly. Even within Latin America, the early participatory budgets (PBs) in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in the 1990s and early 2000s – cited here as one of the most successful examples – were very different from the communal councils and communes developed in Venezuela, or the more sporadic assemblies used in Bolivia, a few years later. Although not part of a wider revolutionary process, the scope of the powers in Porto Alegre was in fact much greater.

It would be foolish, from so far away, to pretend to offer much of an opinion on exactly what might work best in New York City. As these authors point out, it is more important to identify the underlying principles. It is these that will determine whether a given form of assembly democracy can effectively change the relations of power, and whether it really can, or even wants to, open up possible paths to a different kind of society.

The problem is that the principles they do identify are quite slight and could lead in a rather different direction. This is not semantic quibbling: the gap between ‘affecting decisions’ and exercising sovereign power is the gap between supplicants and rulers, between consultation theatre and the embryo of workers’ self-government. They are significantly weaker than the four core principles adopted by the founders of Porto Alegre’s participatory budgeting. For example, Hetland and Sunkara talk about ordinary people having “real and meaningful opportunities to affect the decisions that shape their lives”, and counterpose this to the “participation without influence” that breeds cynicism about many exercises in participation that are merely consultative. This distinction is important, because many later versions of participatory budgeting were indeed consultations without real power. But the original Porto Alegre version was stronger still. Its second and third core principles were that (2) the PB should have sovereign decision-making power, and (3) that it should discuss the whole budget, not just a sliver of it. This sounds like a lot more than just ‘affecting’ decisions.

The first of the Porto Alegre core principles was that (1) the PB should be based on direct, universal participation. The basic building block was mass, local assemblies, where all citizens could take part – there were no delegates at this level of the process, and certainly no algorithms performing random selection or sortition – and where they could debate and decide on the main priorities. An elected PB Council would then work out the nuts and bolts. This partly overlaps with Hetland and Sunkara’s second principle, where they talk about creating spaces “to foster meaningful deliberation”. As they rightly observe, this “is how non-elites learn to govern themselves”, bringing working-class communities together across the divides of race, gender and language that often separate them. This is the essence of collective action, and it upends the isolation and atomisation that underpins most of our capitalist societies.

The fourth Porto Alegre principle was that (4) the PB process should be self-regulating. Its shape and procedures, its rules, would not be decided by anyone else or laid down in legislation by some other body. The assemblies and their elected council would work out the rules and keep changing them along the way as needed. There is at least a potential contradiction between this fundamental autonomy and the third principle our authors suggest for the new Mamdani administration. They talk about the need for a “deliberate design” to avoid the participatory space reproducing inequalities of confidence and political experience, or becoming dominated by existing activists.

These are issues that have drawn attention within our own process of launching Your Party. Certainly, most would agree on the importance of taking steps to make political spaces – in this case the assemblies of participatory democracy – as accessible as possible, in relation to physical accessibility, child care, procedures, language, tone and so on. The problem is that these needs have also been used to justify a ‘deliberate design’ drawn up somewhere else according to criteria decided by no-one quite knows who. And this in turn raises suspicions of algorithms shaping representative samples, sortition and digital plebiscites. Such instruments, whose roots lie more in marketing and management studies, tend to reproduce the prevailing isolation of individuals, rather than foster the kinds of collective action that alone can begin to reverse the relations of power.

It is worth remembering that most of the core group that ‘invented’ the Porto Alegre experience saw themselves as revolutionary socialists. They were members of the Democracia Socialista current in the Workers Party (PT), which was then the Brazilian section of the Fourth International. When they suddenly found themselves at the head of the city hall administration in a medium-sized state capital, they asked themselves how they could use this to move towards a revolutionary overthrow of the capitalist state. And the first experience they turned to for possible inspiration was the Paris Commune.

Their conception of the participatory budget, and more broadly of direct, assembly-based democracy, was developed with this in mind. As a co-thinker of theirs in France, Catherine Samary, later put it, participatory democracy can be revolutionary if it permanently challenges the existing structures of the bourgeois state. If it ceases to challenge them, if it merely complements or ‘extends’ the processes of existing representative democracy, it becomes merely reformist and can easily be co-opted as a block to radical change and in effect a prop for the status quo.

Anyone who has endured a local council’s ‘community engagement’ session already knows where this leads: sticky notes on flip charts, facilitators with lanyards, and outcomes decided months ago by officers now nodding gravely at your contributions. That is why, not long after the successes of the early, radical participatory budget in Porto Alegre, the World Bank was soon promoting a watered-down, consultative version as a pillar of ‘good governance’ in the Global South. Although the situation in New York today may be very different, similar dilemmas, and dangers, are likely face any attempts by the new mayor to open up popular assemblies and spaces for participatory democracy. We should pay close attention because, with a bit of luck, we might later have to deal with parallel problems here in Glasgow.

Iain Bruce, is a member of Your Party in Glasgow North

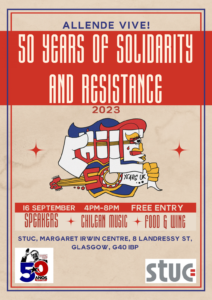

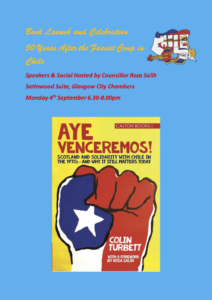

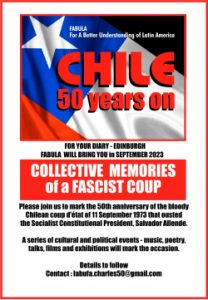

Programme still in development for September 2023 with participation of FABULA ( For A Better Understanding of Latin America ) Full details here:

Programme still in development for September 2023 with participation of FABULA ( For A Better Understanding of Latin America ) Full details here: