If dire warnings resolved the environmental crisis we would be heading for victory writes Alan Thornett.

Boris Johnson tells us that we are heading for a new dark ages, which indeed we probably are. The UN Secretary-General has called it a “code red for humanity”. A report from the IPCC (International Panel on Climate Change), just before the Glasgow COP concluded that changes to the Earth’s climate are now “widespread, rapid, and intensifying”.

Such warnings are important, of course, but the gap between such words and action is enormous. At the moment we are heading for a 2.7 degC increase by the end of the century – which would be catastrophic – and that is only if countries meet all of the pledges they made in Paris.

The problem in Glasgow is not just whether an agreement is reached, or even whether it will be implemented, it is that the target that has been set by the elites – ‘a 50 per cent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 and then ‘net’ zero by 2050’ – was entirely inadequate before the conference opened.

The 1.5degC limit was a last-minute breakthrough at the Paris COP in 2015, and was agreed only as an aspiration and not a policy. Two years later (in October 2018) it was officially adopted in a Special Report on Global Warming published by the IPCC. The Report concluded that the 1.5degC limit was entirely possible within the laws of chemistry and physics but would require unprecedented effort in all aspects of society to implement. The IPCC also warned that we have just 12 years to do something about it, since a 1.5degC increase could be reached as soon as 2030.

After this the climate movement then adopted the slogan net zero by 2030 – which was adopted by the 2019 LP conference, for example, with the ‘net’ part hotly disputed. The resolution was supported by the UNITE union. Extinction Rebellion (XR) adopted it with a date of 2025.

Zero carbon by 2030, however, has been replaced in Glasgow by a demand for a ‘50 per cent carbon reduction by 2030 and net zero by 2050’. The British government has adopted this position and according to Ed Miliband Labour has also, with 2040 instead of 2050.

We should reject the notion that that zero carbon by 2030 can’t be done – from whoever it comes. It would, of course, need a dramatically new approach and degree of political will commensurate with an existential threat. And it would have to be led by governments, who alone have the resources to do it. It means putting their economies on a war footing – a point made strongly (and bizarrely) by the heir to the British throne.

During the Second World War the British economy was taken over by the government and completely turned over to war production within months.

The USA acted in the same way once it entered the war. The US War Museum puts it this way: “Meeting these (wartime) challenges would require massive government spending, conversion of existing industries to wartime production, construction of huge new factories, changes in consumption, and restrictions on many aspects of American life. Government, industry, and labour would need to cooperate. Contributions from all Americans, young and old, men and women, would be necessary to build up what President Roosevelt called the “Arsenal of Democracy.”

Leaving aside the jingoism, the scale of the ecological emergency also requires mobilisations of this kind which go way beyond anything that the free market can achieve – despite the profile it has been given in Glasgow.

It means forcing major structural changes at every level of society very quickly. It means a major transfer of wealth to the impoverished countries to facilitate their transition and lift them towards western levels of development. It also means major reductions in energy usage and wastage alongside renewable energy. It also means recognising that this decade – the 2020s – is crucial in all this. Once we go beyond this decade the problems escalate and the task becomes more difficult.

As Greta Thunberg insisted in the Guardian last month: “Science doesn’t lie. If we are to stay below the targets set in the 2015 Paris agreement – and thereby minimise the risks of setting off irreversible chain reactions beyond human control – we need immediate, drastic, annual emission reductions unlike anything the world has ever seen. And since we don’t have the technological solutions which alone will do anything close to that in the foreseeable future, it means we have to make fundamental changes to our society.”

Increasing public support

Last month a poll of 22,000 people, conducted by Demos, found that up to 94% public supported radical action to stop climate change including a carbon tax on industry, a levy on flying, a speed limit of 60mph on motorways, and a campaign to reduce meat eating by 10%. Last week another poll of 35,000 people, this time by GlobeScan, found that a big majority want their governments to take tough action against climate change.

Protest actions have also greatly increased. Not only those around the Greta Thunburg, the remarkable school strikes, and the Fridays for Futures movement, but around XR and Insulate Britain who have played a major role in the run-up to Glasgow.

Last week 49 members of Insulate Britain were arrested after the group blocked three major junctions in London as part of an ongoing campaign in defiance of injunctions banning them from protesting anywhere on England’s strategic road network. The group, is calling on the government to commit to insulate all British homes by 2030 as a key step to tackling the climate crisis. Along with XR in particular they have played a major role in mobilising public opinion in the run-up to Glasgow.

Alongside this science is telling us that we have 10 years to hold the global temperature increase to a maximum of 1.5degC. After that a dangerous and irreversible feedback process could take un-challengeable control.

How all this will affect the outcome in Glasgow, however, remains to be seen over the next two weeks. Many world leaders, heading for summit, were already more concerned with how they can get away with pledging as little as possible and how many loopholes and excuses they can deploy to avoid serious action.

Johnson – a dangerous liability

Any gains that might come out of this conference will be in spite of Boris Johnson, who was deeply discredited on environmental issues well before he got there – even in capitalist terms.

He acts as if he is a lifelong environmentalist dedicated to the defence of the planet when most of the time he acts as a climate sceptic and runs a party that is stacked out with climate sceptics. Other than supporting electric cars – though in a totally under resourced way – his domestic record on environmental issues is appallingly

In the UK budget last week – you couldn’t make it up – he actually reduces the tax on domestic air travel– a more direct snub to COP26 it is hard to imagine. He is also supporting the development of a major new oil field in the North Sea off Shetland [Cambo] with an estimated capacity of more than 1,000-bn barrels. He continues to defend the opening of a new deep coal mine in Cumbria – which he claims is nothing to do with him. (Britain is currently producing 570m barrels of oil and gas a year and has a further 4.4bn barrels of oil and gas reserves to be extracted from its continental shelf.)

His huge road building programmes, alongside airport expansions, are still on his government’s agenda. He cut Britain’s foreign aid budget from 0.7% to 0.5% of GDP in advance of this COP26. His government has refused to prevent the water companies dumping millions of tonnes of raw sewage a year into UK rivers making them amongst the most polluted in Europe.

His biggest lie, however, is his oft repeated claim that Britain has reduced its carbon emissions by 44 per cent since 1990.

This is only true if you exclude the embedded emissions that Britain has exported to China and India and other developing countries as a result of massive de-industrialisation. The emissions from which now appear in the carbon budgets on those countries not the UK. Britain also excludes from its figure carbon emissions from to major emitters, aviation and shipping. These exclusions have a huge effect, amounting to around 50 per cent of Britain’s carbon budget.

(Johnson also arrived at the G20 in Rome banging his little Englander drum after flouting the agreement he signed with the EU in terms of the access of goods into the north of Ireland and French fishing rights around the Channel Islands, in order to boost his support amongst UK Brexiteers.)

Conclusion

Despite it self-evident weakness, and its inability to reach conclusions and take actions commensurate to the problem the COP conferences are important in raising global awareness of the problems and as a focal point of struggle for real and decisive action. The climate movement is right to take these conference seriously and to place demands on them that would begin to have positive results. Those who argue that we (the movement) should have nothing to do with the process should think again.

Stopping climate change and environmental destruction, however, will not be resolved by COP conferences but will require the broadest possible coalition of forces ever built – and the struggle around the COP conferences is important in building such a movement.

Such a movement must include vast range of activists from those defending the forests and the fresh water resources to those that are resisting the damming of rivers that destroy the existing ecosystems. It must include the indigenous peoples who have been the backbone of so many of these struggles along with the young school strikers, and those supporting them who have been so inspirational over the past two years. And it should include the activists of XR who have brought new energy into the movement over the same period of time.

It will also need to embrace the more radical Green Parties alongside the big NGOs such as Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, WWF, the RSPB, which have grown and radicalised in recent years alongside the newer groupings that have come on the scene such as Avaaz and 38 Degrees. These organisations have radicalised, particularly in the run up to Paris, and have an impressive mobilising ability. Such a movement has to look wider, to embrace the trade union movement, and also the indigenous peoples around the world along with major social movements, such as La Via Campesina and the Brazilian Landless Workers Movement (MST).

The involvement of the trade unions is also crucial, though it remains difficult in such a defensive period. Progress has been made, however, via initiatives such as the campaign for a Million Green Jobs in Britain, which has the support of most major trade unions and the TUC, and the ‘just transition’ campaign (i.e. a socially just transition from fossil fuel to green jobs) which has the support of the ITUC at the international level, and addresses the issue of job protection in the course of the changeover to renewable energy. This opens the door for a deeper involvement of the trade unions in the ecological struggle.

The real test, however, will be whether it can embrace a much wider movement as the crisis develops drawing in the many millions who have not been climate activists but are driven to resist by the impact of the crisis on their lives and their chances of survival.

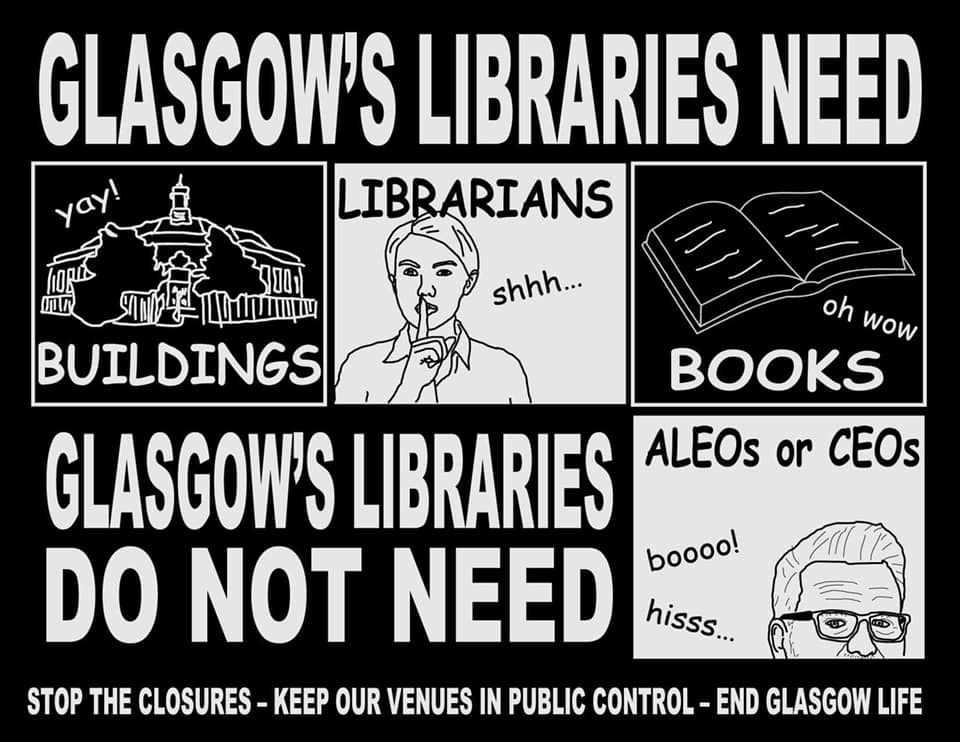

Rather than close facilities directly, the Council plans to squeeze funding forcing Glasgow Life to declare facilities are unviable and offer to hand them over instead to “community trusts” through a “Community Asset Transfer”. This means that instead of being run by the Council, using professional staff and having municipal-level economies of scale, small groups of volunteers will need to fundraise to support essential facilities like libraries and community centres. It’s a nasty trick that’s long been used by the Tories in England, aided and abetted by Labour councils like those in Birmingham and Waltham Forest. The elected politicians wash their hands of the services by handing control over which stay open or go to unelected officers, and rely on the “goodwill” and voluntary efforts of community groups to keep services going.

Rather than close facilities directly, the Council plans to squeeze funding forcing Glasgow Life to declare facilities are unviable and offer to hand them over instead to “community trusts” through a “Community Asset Transfer”. This means that instead of being run by the Council, using professional staff and having municipal-level economies of scale, small groups of volunteers will need to fundraise to support essential facilities like libraries and community centres. It’s a nasty trick that’s long been used by the Tories in England, aided and abetted by Labour councils like those in Birmingham and Waltham Forest. The elected politicians wash their hands of the services by handing control over which stay open or go to unelected officers, and rely on the “goodwill” and voluntary efforts of community groups to keep services going. demonstration on Saturday marched from the City’s shopping area, under the watchful gaze of the statue of Labour politician Donald Dewar, to the People’s Palace in Glasgow Green to hear speakers protesting against the cuts. While there were a lot of lefty paper sellers selling their wares to each other, the important element in the protest was the engagement from local community activists like the campaigns in Drumchapel, Ruchill, Maryhill and Whiteinch parts of the City, alongside support from union members especially members of

demonstration on Saturday marched from the City’s shopping area, under the watchful gaze of the statue of Labour politician Donald Dewar, to the People’s Palace in Glasgow Green to hear speakers protesting against the cuts. While there were a lot of lefty paper sellers selling their wares to each other, the important element in the protest was the engagement from local community activists like the campaigns in Drumchapel, Ruchill, Maryhill and Whiteinch parts of the City, alongside support from union members especially members of