Alan Thornett writes on his Ecosocialist Discussion blog https://www.ecosocialistdiscussion.com/ .

This is a revised version of chapter 16 of my book Facing the Apocalypse–Arguments for Ecosocialism, published in 2019, which might be useful today in the current debates on the role of agriculture.

In 2007 and 2008, dramatic increases in world food prices created economic instability and social unrest, in the poorest regions of the world. Those ‘normally’ subjected to famine and starvation were joined by seventy-five million more.

It was this that triggered the Tunisian revolution in January 2011, which led to the Arab Spring.

A young Tunisian vegetable seller, the lone breadwinner of a family of seven, set himself on fire in front of a government building after police confiscated his unauthorised cartload of vegetables. It was followed by protests over food prices as well as corruption, social inequalities, unemployment and political repression.

In the Global South today, over 800 million people are malnourished and 40 million die every year from hunger or diseases caused by hunger. Another 2 billion people have no regular access to clean drinking water, and 25 million die every year as a result. Sixty-six million primary children go to school hungry across the developing world—23 millions of them in Africa.

The plight of these countries is compounded by the domination of the WTO the IMF and the World Bank. These are the neoliberal gatekeepers that have saddled them with massive debt and forced them to produce monoculture crops for the multi-national companies whilst their own farmers are bankrupt by subsidised competition from the Global North.

This destroys the economic and social conditions of these countries and distorts the markets in which they operate, and leaves them powerless to comate the gathering climate catastrophe.

Meanwhile, desertification, salinification and floods are making large areas of the planet unsuitable for growing food. Climate chaos is creating extreme weather events, in which loss of life and destruction of dwellings and infrastructure have inflicted death, disease and further poverty on millions.

The big question

The salient question, therefore, is not just whether enough food can be produced, and distributed, to feed the existing human population of 7 billion (now 8bn-AT), or indeed the 9 or 10 billion people projected by mid-century without destroying the biosphere of the planet in the process. In other words without a massive extension of industrialised/intensified agriculture and by the ever-increasing use of artificial fertilisers, pesticides, hormones, antibiotics, and mono-cropping techniques?

Already, 60 per cent of current global biodiversity loss—i.e. the sixth great extinction of species that we are witnessing—is directly due to food production including the catastrophic destruction taking place the Amazonian rain forest, the most environmentally rich and diverse habitat on the planet.

At the same time agriculture is a massive contributor to GHG emissions, including methane from livestock, nitrous oxide from the soil, CO2 from machinery. Perhaps the most remarkable statistic concerning food production is that the GHG emissions generated by meat production for human consumption are at 17 percent is almost equal to the 20 per cent generated by the entire world-wide transportation system combined: cars, trucks, trains, ships and aircraft! Yes, cars, trucks, trains, ships and aircraft!

Industrialised/intensive farming

Today, 70 billion land animals (i.e. excluding fish) are slaughtered every year for human consumption. This has doubled in the last 50 years, and is set to double again by 2050.

Two-thirds of these are reared by industrialised/intensive methods—or Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)—as they are known in the trade. This requires vast quantities of corn, maize, and soy that could be eaten directly, and far more effectively, by the human population itself. There are now more than 50,000 facilities classified as CAFOs in the US, with another quarter of a million industrial-scale facilities just below that threshold.

In his 2017 book Dead Zone-where the wild things were, Philip Lymbery— who is also author of FARMAGEDDON-the true cost of cheap meat, published in 2014—points to a study by the University of Minnesota found that for every 100 grams of grain fed to animals only a fraction convert into human food: i.e. 43 un the case of milk, 35 with eggs, 40 with chicken, 10 with pork, and just 5 in the case of beef. My contemporaneous review of Dead Zone can be found here.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organisation 2006 Report Livestock’s Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options, concluded that global meat production will more than double to 465 million tonnes by 2050; and that milk production will grow from 580 million tonnes to 1,043 million tonnes in the same period. The environmental impact of livestock production will have to be cut in half, it says, just it concluded just to keep the damage at the present level.

Beef consumption

The average American consumes 120 kg of meat a year, and the average Britain 80 kg. Whilst these levels are stable at the moment, meat consumption in the developing countries is rising rapidly. The global livestock sector currently produces 285 million tonnes of meat altogether—or about 36 kg (80 lb) per person, if divided evenly.

This involves the use of huge quantities of mineral fertiliser and pesticides as well as antibiotics to control the infections that result from confining them in too small a space and of hormones to fatten them faster.

The methane produced by cattle is also huge, putting the equivalent of 2.8 billion tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere. Globally cattle produce 150 billion gallons of methane every day from their digestive processes—and methane is 86 times more potent as a GHG than CO2.

In their 2016 film Cowspiracy Kip Anderson and Keegan Kuhn concluded that livestock along with their feed, their waste, and their flatulence account for up to 32 billion tonnes of CO2 per year, or 51 per cent of all worldwide CO2 equivalents. Livestock also generate 53 per cent of all emissions of nitrous oxide (mostly from manure) which is a greenhouse gas with 298 times the warming potential of CO2.

Soy beans and palm oil

Between 1960 and 2009, global soy production increased by nearly ten-fold, and it has doubled again since then. The USA used to be the major producer of produce of soy, but there has since been explosive growth in Latin America, particularly in Brazil. Today, China, at 55 million tonnes, is by far the biggest importer of soybeans and is expected to increase its imports by 5 per cent a year. Soy bean imports to Asia are also expected to grow from approximately 75 million tonnes in 2009 to 130 million tonnes in 2019.

The global palm oil trade is worth $40 billion a year, accounting for over 30 per cent of the world’s vegetable oil production. Malaysia and Indonesia are now the two biggest palm oil producing countries and are rapidly replacing their abundant rainforests with oil palm plantations. They account for 84 per cent of the worlds palm oil production. In South America palm oil production has recently increased in Colombia, Ecuador and Guatemala. The second largest global vegetable oil, soya, takes up 120 million hectares, producing 48 million tonnes of soya oil.

Chickenisation

If red meat is the most damaging to the planet, that does not mean that mass produced chicken is a benign product. Lymbery calls this chickenisation, and points out that around 60 billion chickens a year are currently produced for meat. It comes, he says, at a terrible cost to the birds as well as massive pollution of the environment.

He points out that:

Poultry meat and eggs are a major source of infection from another serious food-poisoning bug: salmonella. Keeping chickens in large flocks or in cages can dramatically boost the risk: studies have shown that caged hens are up to ten times more at risk of salmonella than birds kept free-range… Farmers routinely attempt to safeguard their birds against such bugs by dosing them with antibiotics… Indeed, half of all the antibiotics produced in the world are fed to chickens, cows, pigs and other farmed animals.

There are serious implications in this for human health in terms of antibiotic immunity.

Oceanic Dead zones

Philip Lymbery—as the tile of his book suggests—also points in some detail to the development of oceanic dead zones, or hypoxia as they are scientifically known, in what is possibly the most terrifying upshot of meat production. They are caused by agricultural run-off which often reach the sea via the river systems. They are not new but they are now multiplying rapidly.

He focuses on a dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico that forms every year from February to October, and is the second biggest in the world. Dead zones are generated by a lack of oxygen, creating a lifeless bottom layer of water which most creatures are unable to tolerate. Bottom-dwelling animals with no escape – crustaceans for example – are wiped out.

Lymbery points out that the number of dead zones around the world doubles every decade. There are now more than 400 dead zones covering some 95,000 square miles. Most are found in temperate waters off the coast of the USA and Europe. Some are also brewing in the waters off China, Japan, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand. The biggest in the world is in the Baltic. The Gulf of Mexico dead zone stretches from the shores of Louisiana to the upper Texan coast, covering an area the size of Wales.

The responsibility for dead zones, Lymbery says, is clear. It is the fertilizer used to produces the vast grain crops of the American Mid-West—an area of intensive corn and soya production where large amounts of nitrogen are applied to the soil every year to produce grain mainly for meat production. Whilst 160 million tons of nitrogen is produced every year for agricultural purposes, only a fraction of that which is spread on the fields ends up being absorbed by the crops: the rest ends up as run-off.

The run-off that feeds the Gulf of Mexico dead zone originates in the American Mid-West and arrives via the Mississippi River. The Mississippi drains from land in more than 30 states, making it by far the biggest drainage system in North America. Nitrogen applied to the vast cornfields of the Mid-West to increase the crop yield makes its way through the tributaries upstream into the Mississippi itself, and on into the Gulf of Mexico to fuel the dead zone. The more nitrogen is applied to the crops, the bigger the resulting dead zone.

Fresh water consumption

Another massive impact that agriculture on the planet has been it relentless consumption of fresh water.

Fred Pearce, in When the Rivers Run Dry points out, for example, contends that it takes between 2,000 and 5,000 litres of water to grow one kilo of rice. That is more water than most households use in a week. It takes 1,000 litres to grow a kilo of wheat and 500 for a kilo of potatoes. And when it comes to feeding grain to livestock to produce meat and milk, the numbers become even more startling.

It takes 24,000 litres to grow the feed to produce a kilo of beef, and between 2,000 and 4,000 litres for a cow to produce a litre of milk. It takes 5,000 litres to produce a kilo of cheese and 3,000 litres to produce a kilo of sugar. It takes around 2,000 litres to produce a kilo jar of coffee, around 250 litres to produce a glass of wine or a pint of beer, and a staggering 2,000 litres to produce a glass of brandy.

He argued that:

The water footprint of Western countries on the rest of the world deserves to become a serious issue. Whenever you buy a T-shirt made of Pakistani cotton, eat Thai rice, or drink coffee from Central America, you are influencing the hydrology of those region—taking a share of the River Indus, the Mekong or the Costa Rican rains. You may also be helping the rivers run dry.

He introduces the concept of ‘virtual water’—the water used in the production or manufacture of a product. Those countries exporting such products, he argues, are in fact exporting ‘virtual water’. The USA, he says, is rapidly depleting crucial underground water reserves in order to export a staggering 100 cubic kilometres of virtual water in beef production alone. Other major exporters of virtual water include Canada (grain), Australia (cotton), Argentina (beef) and Thailand (rice).

The agricultural transition

During the twentieth century, agriculture underwent what is known as the agricultural transition—ushering in not just fertilisers and pesticides but mechanisation—bringing about the greatest change since agriculture was first developed by human beings some 13,000 years ago.

Today fewer and fewer people are farmers, agriculture employs 1.3 billion men and women: 40 per cent of the working population. Peasants are still the majority of working people in Africa and Asia.

Over the past two decades, in Asia, Africa and Latin America, peasants have faced ‘conservative modernisation’ policies, posing deep challenges to peasant societies in the attempt to adapt them to capitalist globalisation. Land grabs are now global phenomenon, undertaken by local, national and transnational elites as well as investors and speculators, with the complicity of government and or local authorities.

Land grabbing goes hand in hand with increasing control by big business over agriculture and food, through greater control over land, water, seeds and other natural resources. In this race for profit, the private sector has strengthened its control over food production systems, monopolising resources and gaining a dominant position in the decision-making processes.

The countries of the global South are often under the pressure of debt payments that have increased sharply in recent years.

Crucial tipping-points

Philip Lymbery argues that although the planet is remarkably resilient, we are now reaching a tipping point in its ability to take any more punishment; and that agriculture is playing a major role in this, feeding a global population that is now over 7 billion (now 8 billion AT), but swallowing up nearly a half of the planet’s useable land and two-thirds of its fresh water, and inflicting damage on the soil that is vital for the food we eat. As the human population rises, Lymbery argues, ‘so the quest intensifies for more land to cultivate’. Right now, we are in no danger of running out of food (distribution problems not withstanding), but the environmental damage attached to the way we are choosing to produce it may be irreversible.

An area of cereal cropland the size of France and Italy combined will be needed by 2050 to keep pace with the demand for food. Up to a fifth of the world’s remaining forests, he argues, will be gone in the next three decades – much of it to grow crops for feeding animals for the meat trade:

Great swathes of extra cropland look set to join the chemical-soaked arable monocultures of East Anglia in England. The seas of swaying corn in the Midwest of America and soya in Brazil are set fair to extend still further. There’ll be more fields of maize like the ones I saw in rural Asia… The encroachment of agriculture into the remaining wildlands, together with the onward march of industrial farming, will almost certainly cause irreversible damage to biodiversity, forests soil and water.

He is cautious about giving an opinion on the rising human population of the planet, but he is clearly concerned. ‘To me’, he says, ‘the link is obvious. An extra billion people come with 10 billion extra farm animals, together with what that means in terms of land water and soil.’

Throughout human history, he goes on:

for better or for worse, Homo sapiens have outdone all comers, from the magnificent mammals like the bison that roamed the American plains in vast numbers, to birds like the passenger pigeons that once flocked in great grey rivers through the sky, and to species of fellow humans like the Neanderthals. Whatever has stood in our way, and more often just in our reach, we have erased it. Now we have met our match. The great irony is that our most fearsome competitor for food – livestock – has been put there by us.

The conclusion to all this is clear. Although food continues to be produced (globally) by small and medium sized producers, industrialised agriculture is the predominant producer and is now irreplaceable without major changes both in food production and consumption, particularly in regard to the increasing demand for meat.

Food sovereignty

The problem is clear. Big business dominates our global food system. A small handful of large corporations control much of the production, processing, distribution, marketing and retailing of food. This concentration of power enables big businesses to wipe out competition and dictate tough terms to their suppliers. It forces both farmers and consumers into poverty. Under this system, around a billion people are hungry and around 2 billion are obese or overweight.

Peasant and farmer movement across the world are therefore fighting for ‘food sovereignty’—a term coined in 1996 by La Via Campesina.

Food sovereignty, they argue, allows communities to maintain control over the way food is produced, traded and consumed. It seeks to create a food system that is designed to help people and the environment, rather than make profits for multinational corporations.

The food sovereignty movement is a global alliance of farmers, growers, consumers and activists. It is counterposed to the demands of governments around the world for ‘food security’ a concept that instead aims to ensure that the global demand for food is met by free market methods and ever more industrialised faming systems.

La Via Campesina is one of the biggest social movements in the world, bringing together more than 200 million small and medium-scale farmers, landless people, women farmers, indigenous peoples, migrants and agricultural workers from 70 countries. The Brazilian Landless Workers Movement (MST), with 1.5 million members, is one of the biggest components of Via Campesina. It campaigns for access to land by the poor and for land redistribution. It has led land occupations by the rural poor, forcing the Brazilian government to resettle hundreds of thousands of families.

Small farmers lack access to natural resources—in particular land, water and seeds—since most of the best land is in the hands of the big transnational companies, which impose a model of agricultural production designed for export rather than for local consumption. They impose a commercialised, intensive agriculture, that puts economic interests before the needs of people.

Food sovereignty, on the other hand, puts the local agricultural producers at the centre of the system, supporting the right of the people to produce their own food independent of the conditions established by the market. It is about prioritising local and national markets, and reinforcing agriculture by promoting food production, distribution and consumption on the basis of social, economic and environmental sustainability.

The industrial/intensive agriculture model threatens the existence of traditional farming and fishing and small-scale food production. Women have a central role to play: in the Global South they produce 80 per cent of food. At the same time women and children world-wide are the most affected by hunger and famine. In many parts of the Global South, the law denies women the right to own land, and even where they can legally own it, they are denied that right. As a result of this, many individual and groups of women are joining the farmers’ movements to seek protection.

In Latin America those struggling for the rights of indigenous communities and the right to the land often face murderous repression, as in Brazil and Honduras. In Asia, in Africa—for example, in Mali—on all continents, peasant movements lead the mobilisations against land monopolisation.

Peasant women and men, landless people and indigenous peoples, and especially women and youths and precarious farm workers, are dispossessed of their means of subsistence by practices which also destroy the environment. Indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities are excluded from their lands, often by force, making their lives more precarious and in certain cases examples of modern slavery. Although the concept of food sovereignty relates most strongly to the countries of the impoverished Global South, it also exists in the Global North. In fact the first European forum on food sovereignty was held in Krems in Austria in 2011.

La Via Campesina’s seven principles of food sovereignty are as follows:

Food as a basic human right. Everyone must have access to safe, nutritious and culturally appropriate food in sufficient quantity and quality to sustain a healthy life with full human dignity. Each nation should declare that access to food is a constitutional right and guarantee the development of the primary sector to ensure the concrete realisation of this fundamental right.

Agrarian reform. A genuine agrarian reform is necessary which gives landless and farming people – especially women – ownership and control of the land they work and returns territories to indigenous peoples. The right to land must be free of discrimination on the basis of gender, religion, race, social class or ideology; the land belongs to those who work it.

Protecting natural resources. Food Sovereignty entails the sustainable care and use of natural resources, especially land, water, and seeds and livestock breeds. The people who work the land must have the right to practice sustainable management of natural resources, and to conserve biodiversity free of restrictive intellectual property rights. This can only be done from a sound economic basis with security of tenure, healthy soils and reduced use of agrochemicals.

Reorganising the trade in food. Food is first and foremost a source of nutrition and only secondarily an item of trade. National agricultural policies must prioritize production for domestic consumption and food self-sufficiency. Food imports must not displace local production nor depress prices.

Ending the globalisation of hunger. Food sovereignty is undermined by multilateral institutions and by speculative capital. The growing control of multinational corporations over agricultural policies has been facilitated by the economic policies of multilateral organisations such as the WTO, World Bank and IMF. Regulation and taxation of speculative capital, and a strictly enforced Code of Conduct for TNCs, is therefore needed.

Social peace. Everyone has the right to be free from violence. Food must not be used as a weapon. Increasing levels of poverty and marginalisation in the countryside, along with the growing oppression of ethnic minorities and indigenous populations, aggravate situations of injustice and hopelessness. The ongoing displacement, forced urbanisation, repression and increasing incidence of racism against smallholder farmers, cannot be tolerated.

Democratic control. Smallholder farmers must have direct input into formulating agricultural policy at all levels. The UN and its related organisations will have to become more open and democratic for this to become a reality. These principles form the basis of good governance, accountability and equal participation in economic, political and social life, free from all forms of discrimination. Rural women, in particular, must be granted direct and active decision making on food and rural issues.

This article was first published in my book Facing the Apocalypse—arguments for ecosocialism published on December 2019.

George Monbiot

As additional reading on this would strongly recommend George Monbiot published an excellent book last year (2023) entitled: Regenesis—feeding the World Without Devouring the Planet, which picks up some of the themes that I have raised in the above article.

Agriculture, he tells us is: “the most destructive human activity ever to have blighted the Earth”. That “We are farming the planet to death”, and that “agriculture is the greatest single cause of both climate change and species extinction. “This, he says, is the ‘grand dilemma’ we face.” It is a dilemma he confronts fearlessly, and with little regard to who’s toes, or indeed vested interests, he might be trampling on. His alternative vision is the resurgence of nature – and he makes a very strong case for it.

My review of his book can be found here.

Originally published at: https://www.ecosocialistdiscussion.com/2024/03/05/agriculture-is-killing-the-planet/

Alan Thornett is a retired trade union activist and ecosocialist writer. His books ‘Facing the Apocalypse – Arguments for Ecosocialism’ and ‘Militant Years: Car workers’ struggles in the 60s and 70s’ are available from Resistance Books

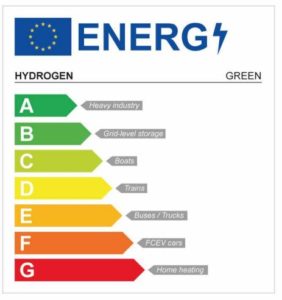

The EU Energy Cities network has actually put together

The EU Energy Cities network has actually put together  William Morris – the outstanding environmentalist in the 19th century – had also gone unheeded when he raged against useless and unnecessary production. In his lecture ‘How We Live and How We Might Live’, delivered in December 1884 in Hammersmith [Image above]– he raised the issue of how to live dignified and fulfilling lives without the need for mass produced commodities and consumerism, and what kind of future society could best provide such an approach.

William Morris – the outstanding environmentalist in the 19th century – had also gone unheeded when he raged against useless and unnecessary production. In his lecture ‘How We Live and How We Might Live’, delivered in December 1884 in Hammersmith [Image above]– he raised the issue of how to live dignified and fulfilling lives without the need for mass produced commodities and consumerism, and what kind of future society could best provide such an approach.

As a global society, we must pursue policies to reduce material consumption and increase our wellbeing. This is the core of degrowth.It is exceptionalism that leads us to think that our

As a global society, we must pursue policies to reduce material consumption and increase our wellbeing. This is the core of degrowth.It is exceptionalism that leads us to think that our