Red-Green Labour’s Sean Thompson gives a cautious welcome to Welsh Labour’s plans.

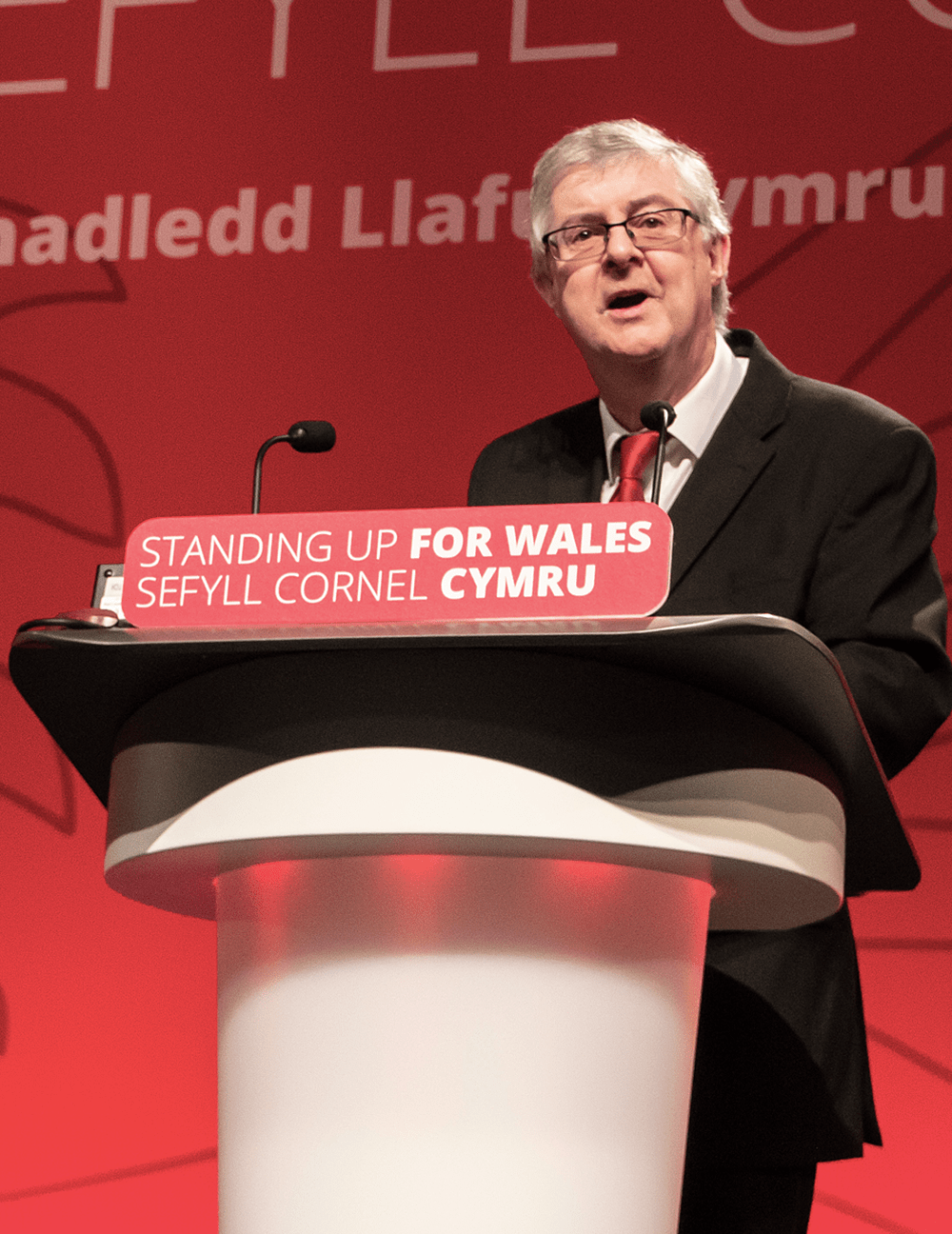

In May’s Welsh Senedd elections, Labour equalled its best result since the Welsh Assembly was established in 1999, winning 30 of the Senedd’s 60 seats. Labour’s manifesto had contained a number of modest, but welcome pledges, including the banning of most single use plastics, the creation of a new national forest stretching the length of the country from North to South and a moratorium on planning permission for large incineration facilities. During the election campaign, the First Minister, Mark Drakeford had repeatedly declared that if re-elected, he would ‘embed our response to the climate and nature emergency in everything we do’.

In May’s Welsh Senedd elections, Labour equalled its best result since the Welsh Assembly was established in 1999, winning 30 of the Senedd’s 60 seats. Labour’s manifesto had contained a number of modest, but welcome pledges, including the banning of most single use plastics, the creation of a new national forest stretching the length of the country from North to South and a moratorium on planning permission for large incineration facilities. During the election campaign, the First Minister, Mark Drakeford had repeatedly declared that if re-elected, he would ‘embed our response to the climate and nature emergency in everything we do’.

Such fine words are to be expected during election campaigns, but all too frequently disappointingly little is done to put them into practice. However, within a week Drakeford announced a major reorganisation of his administration, creating a powerful new Ministry for Climate Change, which has responsibility for transport, housing, planning, regeneration, energy and environment. The Minister and Deputy Minister are, respectively, Julie James and Lee Waters, both on the left of the party, and their key role is stated as being to ‘ensure all Welsh Government policy on new infrastructure projects, energy schemes, and planning decisions can meet environmental targets and be justified in the context of Wales’ current and future climate challenges’. In an early indication of how the new ministry may combine policy areas with the climate crisis in mind, Drakeford announced a commitment to build 20,000 new social homes for rent that will be built to zero-carbon standards, piloting the use of new design and production methods and making use of the underused resource of Welsh timber, currently largely used for pulp.

On 15 June, the administration’s Programme for Government was published, laying out its delivery plan for the next 5 years. Lee Waters has been quite open about his view that the Ministry for Climate Change’s plans are extremely modest in the light of the scale and urgency of the climate crisis, nonetheless they mark a significant step forward both in ambition and recognising the need for a properly integrated programme. In addition to the policies already mentioned, the 2021-26 action plan includes the following main commitments:

- Legislating to abolish the use of more commonly littered single use plastics.

- Introducing a Clean Air Act for Wales, consistent with WHO guidance.

- Maintaining the policy of opposing the extraction of fossil fuels in Wales.

- Supporting the Wales TUC proposals for union members to become Green Reps, with the same rights as H&S Reps, in the workplace.

- Aiming for a 30% target for working remotely.

- Implementing a new 10-year Wales Infrastructure Investment Plan for a zero-carbon economy.

- Reviving the Swansea Tidal Lagoon project as part of a wider’Tidal Lagoon Challenge’ and supporting initiatives that can make Wales a centre of emerging tide and wave technologies.

- Expanding renewable energy generation by public bodies and community groups in Wales by over 100MW by 2026, as well as supporting other community-led initiatives, such as cooperative housing and community land trusts.

- Lifting the ban on local authorities setting up new municipal bus companies, expanding flexible demand-responsive travel across Wales, making 20mph the default speed limit in residential areas throughout Wales and hitting a target of at least 45% of journeys by sustainable modes by 2040.

- Delivering good quality jobs and training through the housing retrofit programme, using local supply chains.

There is much else in the Programme to applaud; strengthening the protections for ancient woodlands, funding additional flood protection for more than 45,000 homes and delivering nature-based flood management in all major river catchments, to expand wetland and woodland habitats, creating a new system of farm support and developing a Wales Community Food Strategy, as well as a commitment to ‘explore options for workers to take an ownership stake in our national transport assets’. However, as ever, words are cheap. Some of the commitments are not entirely in the Welsh Government’s gift, others will, at the very least, be at the very boundaries of the government’s powers – or even beyond them.

For example, the commitment to work towards 30% of office based workers working remotely makes a lot of sense in terms of both encouraging more employment in the valleys of south east Wales or the isolated rural communities of mid and north Wales, as well as helping to reduce the congestion in the major urban areas (pre-Covid, Cardiff had to deal with an influx of over 80,000 commuter vehicles a day, while the antiquated rail services were unbearably overcrowded). However, while the government is proposing a number of sensible measures, such as developing new remote working hubs in former mining communities, they are going to be dependent not only on co-operation – and probably co-funding – with cash strapped local councils, but also on the co-operation of employers. Wales has the largest proportion of its workforce in the public sector of any part of Britain, so getting the active support of local authorities, the NHS and the Higher Education sector is going to be key to the success of the policy.

Supporting, the Wales TUC proposals for Green Reps in the workplace is laudable, however it is beyond the Welsh Government’s devolved powers to enforce it. It will require the government, as part of its Social Partnership policy, to include this reform in the package of fair employment measures it will be seeking to ‘persuade’ employers to accept through the leverage of its (along with the NHS and Higher Education) public procurement muscle.

A number of important measures, such as ensuring that Wales gets its fair share of the Shared Prosperity Fund and the so-called Levelling Up Fund from Whitehall and getting a fair share of vital rail infrastructure and R&D investment for Wales, rely on the the Tories being prepared to spread largesse to the ungrateful Welsh in the manner of Lady Bountiful – an eventuality it would be unwise to hold one’s breath waiting for. And relaunching the Swansea Tidal Lagoon (as it were) would almost certainly require the Treasury (motto: ’Out of my cold dead hand…’) to relax its grip on the Welsh Government’s borrowing limits.

The Tories have always been hostile to the direction that even its current very limited devolved powers have taken Wales, and the performance of the Welsh Government and NHS during the Covid crisis in contrast to the fiasco in England has clearly intensified that hostility. The Westminster Government has already demonstrated that it intends to use the funds meant to replace those from the EU that were devolved to the Welsh Government, that have been so important to the poorest parts of Wales, itself, with (up to now) no consultation with the Welsh Government. Johnson has even threatened that the Westminster Government might seek to impose the environmentally disastrous M4 Extension project, rejected eighteen months ago by the Welsh Government, on Wales as though it was a colony of England (luckily, this idea is about as workable as Johnson’s other wheezes, like the Scotland-Ireland bridge). But in these circumstances, the Welsh Government’s hope that, for example, the under-funded Health and Safety Executive might be devolved to Wales is probably a pipe dream.

Even where the Welsh Government has both the powers and the funding to implement its programme there remains the question of whether it will, in practice, do so. Its record of delivery is patchy. For example, for some years the Welsh Government has – rhetorically at least – had a progressive policy of increasing tree cover in Wales. Since January 2008, under the ‘Plant!’ scheme, a tree has been planted for very child born in Wales (and since 2014, another has been planted in Mbale, Uganda) and the government has had a target of planting 2,000 hectares of new woodland each year. However, since 2013 new woodland has averaged less than 1,000 hectares a year and in 2019/20 just 80 hectares were planted, though the Climate Change Commission estimates that tree planting in Wales needs to be moving towards 5,000 hectares a year if we are to achieve 24% woodland cover by 2050. Given that the idea of a National Forest is Mark Drakeford’s personal vision, one can only hope that the government gets its act together in the most dramatic fashion over the next couple of years.

Another example: the Welsh Government has been committed to a desperately needed green housing retrofit programme for some years. 32% of homes in Wales were built before 1919, we have some of the oldest and least thermally efficient homes in Europe, and there are currently over 250,000 households living in fuel poverty.

But while the Welsh Government has implemented a number of worthwhile initiatives to address these issues, including its Warm Homes Programme, the Welsh Housing Quality Standard and most recently the Optimised Retrofit Programme, these initiatives have largely involved social housing, not privately let or owner occupied homes, though both of those latter sectors are on average in poorer condition. A major programme is needed to retrofit all existing homes in Wales to at least an EPC ‘B’ rating within the next ten years that would not only tackle both greenhouse gas emissions and fuel poverty, but would create thousands of new, well paid, unionised jobs (10,000 FTE jobs a year over 15 years, according to the Institute of Welsh Affairs).

However, as with many of the commitments in the Programme for Government, no targets or timescales for the housing retrofit programme have been published, just statements of good intentions, although given the speed at which the programme has been put together and published since the election in May, that is not entirely surprising. It is vital, though, that those statements of intent are transformed into practical action over the coming months.

Despite the Welsh Government’s less than stellar environmental performance record, the relative modesty of the environmental goals in its new Programme for Government and the increasingly problematic issue of its limited legislative and financial powers under the current devolution settlement, there are reasons to be optimistic. The creation of a new Ministry explicitly concerned with the climate crisis that is responsible for most of the key areas where radical change is needed – including transport, housing, environment and energy – is potentially extraordinarily important. The fact that Drakeford has put this Ministry in the charge of two of his key supporters – both firmly on the left of the party when the majority of Labour MSs (Senedd Members) are on the right – is a hopeful sign that radical action that challenges the status quo may start to creep onto the political agenda.

And evidence that that hope is not totally unfounded was provided on 21 June when Lee Waters announced that all new road building programmes in Wales have been frozen with immediate effect in order to be subject to an independent review. In his announcement, Waters said: ‘I don’t think people realise the amount we have to do. Since 1990 we have reduced emissions by 32% and by the end of the decade we have to more than double that and it’s up again by 2040. We really do have to ramp up what we have been doing. In 10 years, we need to achieve more than the last 30 and in those years we have done the relatively easy things, there is no low hanging fruit. If we’re going to hit this target we’re going to have to do things differently.’

When asked what he would say to people who face regular traffic jams on the roads where schemes have been halted, he said: ‘If we do nothing, we are facing catastrophic consequences for our communities. A lot of this is going to be uncomfortable change and it’s not going to be easy and I am not pretending there’s simple answers. There will be tensions and will be contradictions, we need to make it easier for people to do things that help us tackle climate change…For most people, the reality is that using public transport is not easy and isn’t attractive and we need to change that to make it easier. We can’t do that if we’re spending all our money on road building. We have reached the point where we have to confront the fact we can’t keep doing what we have always done’.

Republished from RedGreen Labour